|

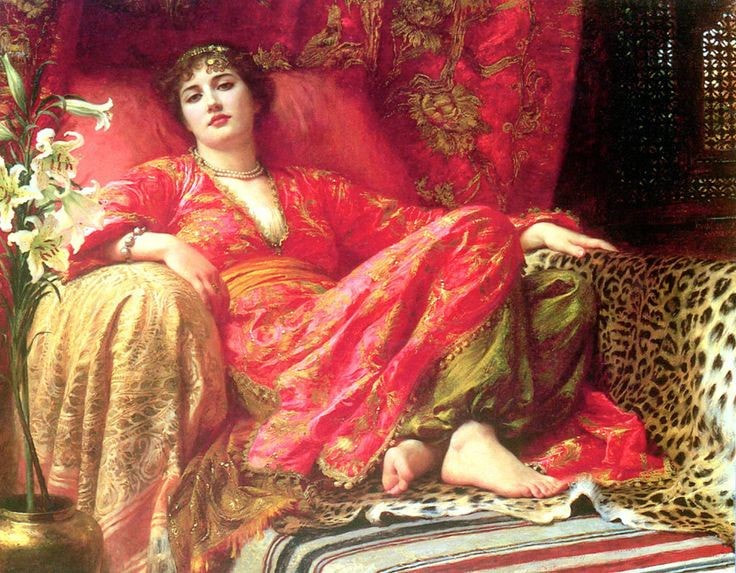

Guest blog by Irene Abdi and Georgette Veerhuis (as also published at rscw.nl) We learned your French. International development: navigating power In this poem, spoken word artist Kyla Jenée Lacey articulates the realities of white privilege in the US and how it ties in with colonialism, slavery, uprootedness, identity and trauma. But also with knowledge. Specifically, Lacey touches upon the colonial politics of knowing: the epistemic violence Europe engaged in through its Eurocentric claim on knowledge and how this still shapes our world today. Reportedly, a teacher from Sullivan County Tennessee was recently fired for showing this poem in his classroom. This goes to show how relevant and dangerous it (still) is to talk about issues of colonialism and race today. Working in the international development sector often means working with underprivileged, oppressed, displaced, or indigenous peoples. The peoples that European history has traditionally trapped in terms of ‘lacking development’ and erased from its pages as conscientious beings. Whether or not this is true, the opposite is most certainly true: development work is about working with (or possibly against) the privileged. Those that keep these complex systems running because it serves them. Development workers are not exempt to this. Indeed, it is no secret that the international development sector is rooted in a violent history of European colonialism, fed by far-reaching geopolitical forces and capitalism, and whitewashed with a problematic mix of white ignorance, guilt and heroism.[1] The not-so-innocent practice of ‘knowledge sharing’ This raises questions about what is arguably one of the most important practices of international cooperation today: knowledge sharing. Now everyone agrees that, at least in theory, knowledge sharing between stakeholders is crucial if interventions are ever to be successful and impact sustainable, and - you know - not actually disruptive of local cultures, economies and biodiversities.[2] And it sounds so happy and easy, too (and positively orientalistic): like we would all sit in a big circle under the stars, the heat of the campfire drawing us closer together while we, encouraged by the jangling beat of a tambourine, share our insights. And after we’d all walk away joyous and enriched, ready to change the world. But that’s not how it is. Knowledge is power, after all. So you’ll need to ask yourself: historically, who is allowed to share? Or better yet, who is ascribed the status of knower? Similarly, who is deemed ignorant and should really only sit back and learn? What even counts as knowledge? And importantly, who decides? In essence, the practice of knowledge sharing is political. As a development worker you have to wonder how these histories inform our current practices and encounters, and try to find answers to the question: how can we engage in knowledge sharing as part of a decolonial praxis, in which stakeholders participate as ontological equals, as knowers on equal footing? Is this even possible? Colonization and other(ed) ways of knowing The late Edward Said, founder of the academic field of postcolonial studies, was one of the first scholars to describe how Europe in the 19th century, as a means to justify its colonial conquest, culturally represented the Middle East by orientalising it. Said (1978:1) called the Orient “almost a European invention; … a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.” Most importantly, it was constructed as a region with distinct and contrasting racial and cultural differences to that of the West. This idea served to elevate the status of white Europe - the Occident - and cemented into its cultural consciousness the imagined inferiority of the exocitized non-white Orient, the ultimate ‘other’. Nowadays this is more commonly known as Eurocentrism: an ideology that takes western civilization as its vantage point, grasping the world with its gaze, and that constructs it as the epitome of human progress in relation to all other, lesser developed, civilizations. The Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano expanded on this idea of cultural repression and the colonization of the imaginary. He (2007:169) explains: “The repression fell, above all, over the modes of knowing, of producing knowledge, of producing perspectives, images and systems of images, symbols, modes of signification, over the resources, patterns, and instruments of formalized and objectivised expression, intellectual or visual.” What is meant by this is that part of Europe’s conquest strategy was to disrupt and deprave colonized peoples of their epistemologies, their ways of knowing. This is what constitutes epistemic violence. This was justified by the claim that, ontologically, they were not human beings of equal standing (Quijano, 2007; Ramose, 2021; Spivak, 1988). Instead they were considered sub-human, closer to nature, hypersexual, childlike, dirty, dumb, degenerate. Colonial science: Enlightened much? During the Enlightenment, western Science was heavily invested in creating the social hierarchies to support this colonial narrative, and anchoring it in a discourse of human nature (Foucault, 1975).[3] At the same time western science framed itself as objective, neutral, and universal. (You see what they did there?) This gave scientific knowledge the power of Truth (Foucault, 1975)! This produced a normalizing force and colonial control that was completely inescapable. Moreover, this type of knowledge was utterly Eurocentric, privileging itself over other/indigenous knowledge systems by marking the latter as primitive, folkloric, unscientific (Knopf, 2015). Originating from this history, it is no surprise that 200 years later the development sector is still largely structured around this form of epistemic violence and colonial thinking. So how should we, as young European professionals in this field, go about decolonizing the field as much as our own thinking? Exclusion in the development sector The omission of indigenous knowledge is inextricably linked to exclusion of indigenous peoples in the development sector as a whole. For decades we have viewed so-called developing countries as countries with a lack of knowledge and its individuals as beneficiaries who passively receive knowledge. And even discussions surrounding the decolonization of development cooperation are still Eurocentric. As Themrise Khan (2021) says: “The discussion around the decolonisation of aid practices is, in reality, extremely one-sided and Western-centric. It rarely includes the perspectives of those in the Global South. Many of us in the South do not agree with or relate to this terminology. In fact, we see it as a further imposition of a white saviour complex, with the powerful West once again deciding what is good for us and how this must be done.” According to Stephanie Kimou (in Cheney, 2020), founder of Populations Works Africa, the experiences and desires of people in ‘well-developed countries’ are prioritised in international development. We see this back in for example how monitoring & evaluation systems are set up, how funds are raised, and how stories are told. As Kimou says: “Rather than developing indicators that are important to them and their funders in Washington or Geneva, NGOs can ask the people they serve about how they define success and then design their programs accordingly.” In like manner, funders ask large INGOs to identify African partners that can implement programmes because they don’t trust locally-rooted organisations who have their own frameworks and ways of working (Kimou in Cheney, 2020). This is a pity because this is a missed opportunity to better understand local cultures and learn what works well in those particular contexts. Etuaptmumk: Two-Eyed Seeing - a solution? This existing Eurocentric paradigm is something that we, as young European professionals in this field, need to address if we want to contribute to a fairer and more inclusive world. That means that we can no longer do what Dominique David Chavez, a descendant of the Arawak Taíno in the Caribbean and a research fellow, describes as the western scientific tradition: “go into communities, get that knowledge and go back to our institutions and disseminate it.” Instead, we may adopt the indigneous approach of Etuaptmumk: Two-Eyed Seeing. Advocate and Mi’kmaw woman, Rebecca Thomas, explains in her Tedx Talk that Two-Eyed Seeing is about including different worldviews. “Two-Eyed Seeing takes the strength of both a colonized world and an indigenous world, and asks that the user sees through both lenses simultaneously… It is the Mi’kmaw understanding of the gift of multiple perspectives, to see multiple contexts simultaneously. … It’s not either/or. It’s both at the same time.” This requires us to play an active part in recovering and including oppressed (indigenous) knowledges in our development practice. Indeed, we would need to reinvent the sector as a space for participatory stakeholder engagement and collaborative learning to achieve sustainable impact. This stretches beyond simply patching up damages done due to centuries of (neo)colonialism by means of a fund or a nice statue. It means restoring the ontological status of Knower of ‘othered’ stakeholders and practicing our own ignorance.[4] Put simply, it means letting go of knowing it all. Then, perhaps, we may truly acknowledge each other. Then, perhaps, we may share our perspectives as equals.

References

[1] Look, for example, at the case of Saartjie Baartmans, the ‘Hottentot Venus’. Also for a reading of the relationship between Africa and the West through this figure: The ghost of Sarah Baartman lives on by Trevor Lwere (2021). [2] Ignorance here refers to ‘not-knowing’ in a sincere, curious manner. We should be wary, however, of reproducing the racist power structures that allow white people to wilfully claim ignorance on racism and colonialism. For more, read White Innocence by Gloria Wekker (2016). [3] For more on this, read this blog by Teba Al-Samarai and Jara Bakx (2021) on development and neocolonialism. [4] Jan Nederveen Pieterse (2010:16) claims that: “Conventionally development has been a monocultural project. Modernization and Westernization were virtually synonyms.” In addition, David H. Lempert (2014) explains how development is often framed in terms of linear progression toward creating modern industrialised societies. In the case of Vietnam, Lempert (2014:1, emphasis added) states: “Development of rural areas and of the peoples and their traditions appeared to have come to mean their elimination or destruction.” Comments are closed.

|

About meMy name is Reinier van Hoffen. U®Reading

Click here for a summary.

Also find the text of a lecture Dr. Achterhuis held at the 2012 Bilderberg conference. Archives

August 2022

|

AddressNachtegaallaan 26

Ede, the Netherlands |

Telephone+31 (0)6 1429 1569

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed