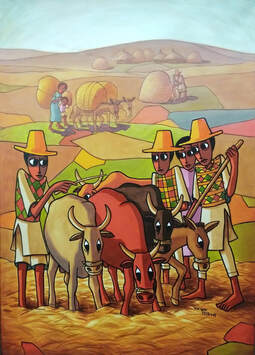

Ethiopian Art depicting the harvest season in Ethiopia (Makush Gallery, Adds Ababa) Ethiopian Art depicting the harvest season in Ethiopia (Makush Gallery, Adds Ababa) Last year, on this blog I published the CIVICUS civic space monitor. Recently, CIVICUS published an update, with civic space quickly disappearing. And if you are an expert on civic space that is an alarming statistic. However, if you are a civilian in the highlands of Ethiopia, civic space is probably the last thing on your mind. Your worries concern the amount of rain and the changing seasonality of it. Or the presence of a locust swarm that eats away your crop. Or that your labour force to harvest the crop is consumed by an armed struggle for self-determination, for better or worse. This may be the situation that a lot of people we met on the road last year may find themselves in during this harvest season. During Christmas holidays as a family we traveled through the highlands of Ethiopia and saw the grain being harvested and the oxes doing their threshing work while others were winnowing the grain by hand with help of the wind. In such a context what is the relevance of civic space? Has the current armed struggle anything to do with civic space, or the lack thereof? Or is something else at play? To answer this question one needs to dig deep into the history of people and places to understand first of all whose space we talk about and secondly how it links to the threshing and winnowing of grain. Screaming loudly about shrinking civic space, as many are doing, may not be the best strategy to get the message across unless you have a clear perspective whose space we are talking about; why we should pay attention to this space; how it is shrinking; and how it affects people's lives to finally arrive at the question: What can be done about it? During our trip last year we took note of the rich history of the Ethiopian highlands by seeing historic sites like Lalibela, Axum and Gondar enjoying marvelous beauty of nature and landscapes and friendly people. I cannot help but share a few pictures below. And though I had heard of the many changes to the road system in Ethiopia (including in its capital Addis Ababa) I was still surprised to find out how a journey from Addis to Dessie that 15 years ago took me a minimum of ten hours over a poorly maintained road was reduced to a six hours journey over a nicely paved road. The drivers were quick to point to all the new factories and/or horticultural farms that had sprung up during recent years and that had significantly influenced the local social economy, bringing a better standard of living for many formerly landless labourers. As we ventured out into the rural area of the highlands of Ethiopia it was harvest season and the grain had been collected and was threshed by the hoofs of oxes and donkeys, with Ethiopian men and women supporting them to keep going. This was mostly done on hilly places where they could subsequently easily separate the wheat from the chaff by just throwing it in the air, the so called winnowing. It struck me that this was still common place in most of the highland area of Ethiopia where mechanization was neither an option nor a desire for the small holder farmer.

Back in the Netherlands I found myself at a New Years reception at our Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Our Minister of Foreign Affairs did his level best to motivate us for the coming year to make a difference and not to forget about the perspective of the potato farmer in remote North-Holland whose export depended on our efforts to broker good export deals. During the Q&A session that followed I felt the need to also bring on board the perspective of the high-land farmer in Ethiopia that I had just met on the road. I of course referenced the 500.000 Ethiopian farmers that we had tried to improve productivity of (see 2018 Dutch development results report) and the close to 4 million households we had helped to stay food secure through a productive safety net program run by the Ethiopian government. So back to the question: Whose space are we talking about when we say that civic space is shrinking? Is it the small-holder farmer who sees his ancestral lands being taken from him with some financial compensation and leased to a foreign investor for a significant period of time, which is most of the time considered to be in the best public interest? Or is it the space of the factory worker who requires good labour conditions from the foreign investor, who was attracted by the availability of cheap labour? Or is it the space of the investor himself? Asking the question is also answering it. Each of them would benefit from increased civic space and all of them have seen it shrinking. Hence we may be talking about competing spaces. So let us examine, how does civic space look like for each of them. Civic space, according to Wikipedia, is "created by a set of universally-accepted rules, which allow people to organise, participate and communicate with each other freely and without hindrance, and in doing so, influence the political and social structures around them". However it continues to say: "It is a concept central to any open and democratic society and means that states have a duty to protect people while respecting and facilitating the fundamental rights to associate, assemble peacefully and express views and opinions." What if these rights are exercised by different groups with competing interests? The farmers who have a customary right to cultivate the land and have organized themselves, possibly with some public or private support, in cooperatives. They are facing the challenges of shrinking rural space for an expanding population. Lands may have seen over cultivation, and succession has been problematic since youngsters have been allowed to go to school and have come to know about other ways to earn a living that may allow them to explore the world a bit further. The landless people who did go out to the cities in search of employment were happy to find some employment in neighbouring commercial farms or factories. However, the salaries are just enough to live and too much to die and there are long working ours, whereas they still carry memories of low-season with abundant time to enjoy life. Finally there are those who remain unemployed for whom not a proper job exists and who lack the skills to create a job for themselves, hence they have to rely on petty trade and amongst them many girls may sell their bodies in order to feed their sibblings. In the meantime factory owners are facing increasing insecurity due to the large number of unemployed people that have to go out and steal their living together. Hence, how can all these spaces be negotiated when their interests seem to be so much in conflict with one another and peaceful co-existence seems impossible? Underpinning civic space is a strong social contract between governments and citizens. Shrinking space is often caused by a deteriorating social contract. Awareness about the lack of space or the absence of a social contract when investing in a developing country should be at the center of support provided to Dutch entrepreneurs who are venturing out into these for them unknown territories. Rebuilding that social contract as part of the investment strategy should be part of the equation and would be a great risk mitigation measure. In Ethiopia I have seen some entrepreneurs doing that very successfully, to the extend that local communities defended farms that were under attack of angry mobs of youngsters that lacked local opportunities and felt deserted by their own government. Also governments could invest in a better dialogue around utilization of natural resources and how to best serve the interest of the people. This dialogue should be supported by evidence about current land-use practices, as not all interests are always considered. Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships could be established with public and private entities meeting around some of these wicked problems and negotiating a solution that works for everyone. In the end the what is civic space boils down to the question: whose space are we talking about and could space of one group be limiting the space of others? Who should be mediating the potential conflicts? Here I do see a role for governments, civil society organisations and knowledge institutions, doing fact-finding missions around these conflicts. This may help re-establish a social contract that increasingly also needs to be made between different groups of people within society and governing bodies taking more of a facilitating role. In the end, awareness may raise that conflict will jeopardize everyone's space and will always provide a sub-optimal solution as conflict breeds conflict. Having a clear understanding of different histories of people and a clear view on the competing interests and having all of them considered at the decision-making table in a transparent and open manner may help to keep civic space open for everyone and make it productive towards a stronger social contract. In the end we have to live together in this world where there still is enough for everyone. However, also at global level this requires a new social contract between different people groups that allows us to know each other's history, coming to terms with the disparities that seperated us in the past and present and plan together for a more just global future where burdens are shared and challenges are faced together to the benefit of all. |

About meMy name is Reinier van Hoffen. U®Reading

Click here for a summary.

Also find the text of a lecture Dr. Achterhuis held at the 2012 Bilderberg conference. Archives

August 2022

|

AddressNachtegaallaan 26

Ede, the Netherlands |

Telephone+31 (0)6 1429 1569

|

info@uraide.nl

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed