|

Summer breaks always invite for reflection. Often people take summer courses to gain some new insights in a relevant field of expertise linked to their personal or professional life. While there were a few good summer courses around this summer, I abstained and instead share with you what my chicken taught me over the summer break.

First of all, I have to admit, I have a little bit of a personal attachment to our chicken. Not that they are particularly beautiful or treat me friendly (they make a lot of noise in the morning). It is just that I got used to having to clean their mess every other week. Actually, I should do this more often, as I learned that chicken thrive in a clean environment (as most people do). That raises the question why they are themselves creating such a mess out of their water and food rations. The water tower next to the food tower provide enough and the chicken have really no other business but to bend their necks and pick from both the grain and drink from the water. Still apparently they like to trample the edge of the tower, as an inbuilt mechanism to get the worms out of the soil, messing around with the food, and making the water dirty. I bought these white leghorns a couple of years ago after constructing a chicken run from the remains of a shed. They turn out to be very productive chicken supplying us their 3 eggs almost every day over the last two years. However, despite this welcome addition to our daily diet, I wondered how I could reduce the food and water spills and make the chicken more effective. What did I do wrong? I tried to hang the towers a couple of inches above the soil, so that they could not easily trample the food, to no avail. Not only did their behavior result in food and water losses, but also it causes the soil of the chicken run to be covered with grain, giving me hard time when cleaning up the place. Nowadays there is internet pages full of forums with people sharing their passions on anything. Hence I also found some 'friends' and consulted them on what to do. It quickly appeared that I am not the only one trying to make their chicken behave. Failing to take proper care of a couple chicken makes me humbled in judging the commercial farming practice, that is critiqued by many of my fellow citizens today. Still there is something weird in trying to make chicken behave. Even the so called pecking order disturbed me to some extend, resulting in the early demise of one of them. Today I was so fed up that I took the dominant one apart, allowing the weaker one to eat first. How come I am trying to challenge the laws of nature? Do we not do the same as people? Why did I make these chicken dependent on my supply of food to a nicely contained chicken run while I could have opted to have them roam around in our garden (having them ruining it and having to fetch them from the neighbors or the street every now and then). It appears we want to model the world to our own liking. Serving us with a steady supply of food while minimizing disturbances to our direct surrounding. As I tried to teach my chicken other behavior I realized they may have given me the best summer course I could have wished for. Allow nature to take its course, facilitate people to make their own decisions, and allow maximum space for animals with whom we try to live in symbiosis, and deal with the disturbances this provides to our direct vicinity or turn it into a peaceful co-existence as I learned from the highland communities in Ethiopia. There is no escape from the laws of nature. We better comply.

0 Comments

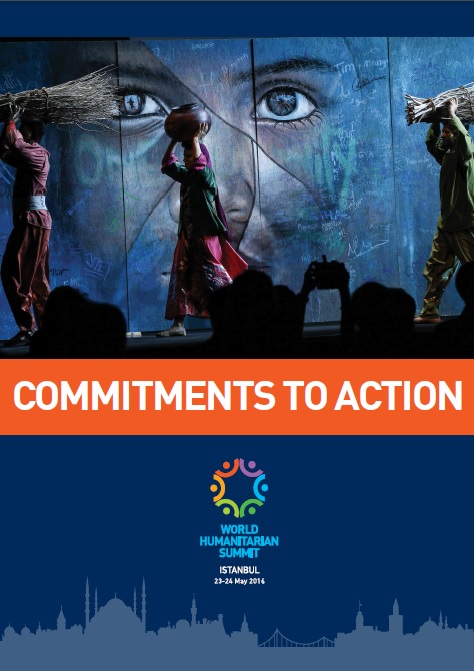

Guest blog by Irene Abdi and Georgette Veerhuis (as also published at rscw.nl) We learned your French. International development: navigating power In this poem, spoken word artist Kyla Jenée Lacey articulates the realities of white privilege in the US and how it ties in with colonialism, slavery, uprootedness, identity and trauma. But also with knowledge. Specifically, Lacey touches upon the colonial politics of knowing: the epistemic violence Europe engaged in through its Eurocentric claim on knowledge and how this still shapes our world today. Reportedly, a teacher from Sullivan County Tennessee was recently fired for showing this poem in his classroom. This goes to show how relevant and dangerous it (still) is to talk about issues of colonialism and race today. Working in the international development sector often means working with underprivileged, oppressed, displaced, or indigenous peoples. The peoples that European history has traditionally trapped in terms of ‘lacking development’ and erased from its pages as conscientious beings. Whether or not this is true, the opposite is most certainly true: development work is about working with (or possibly against) the privileged. Those that keep these complex systems running because it serves them. Development workers are not exempt to this. Indeed, it is no secret that the international development sector is rooted in a violent history of European colonialism, fed by far-reaching geopolitical forces and capitalism, and whitewashed with a problematic mix of white ignorance, guilt and heroism.[1] The not-so-innocent practice of ‘knowledge sharing’ This raises questions about what is arguably one of the most important practices of international cooperation today: knowledge sharing. Now everyone agrees that, at least in theory, knowledge sharing between stakeholders is crucial if interventions are ever to be successful and impact sustainable, and - you know - not actually disruptive of local cultures, economies and biodiversities.[2] And it sounds so happy and easy, too (and positively orientalistic): like we would all sit in a big circle under the stars, the heat of the campfire drawing us closer together while we, encouraged by the jangling beat of a tambourine, share our insights. And after we’d all walk away joyous and enriched, ready to change the world. But that’s not how it is. Knowledge is power, after all. So you’ll need to ask yourself: historically, who is allowed to share? Or better yet, who is ascribed the status of knower? Similarly, who is deemed ignorant and should really only sit back and learn? What even counts as knowledge? And importantly, who decides? In essence, the practice of knowledge sharing is political. As a development worker you have to wonder how these histories inform our current practices and encounters, and try to find answers to the question: how can we engage in knowledge sharing as part of a decolonial praxis, in which stakeholders participate as ontological equals, as knowers on equal footing? Is this even possible? Colonization and other(ed) ways of knowing The late Edward Said, founder of the academic field of postcolonial studies, was one of the first scholars to describe how Europe in the 19th century, as a means to justify its colonial conquest, culturally represented the Middle East by orientalising it. Said (1978:1) called the Orient “almost a European invention; … a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.” Most importantly, it was constructed as a region with distinct and contrasting racial and cultural differences to that of the West. This idea served to elevate the status of white Europe - the Occident - and cemented into its cultural consciousness the imagined inferiority of the exocitized non-white Orient, the ultimate ‘other’. Nowadays this is more commonly known as Eurocentrism: an ideology that takes western civilization as its vantage point, grasping the world with its gaze, and that constructs it as the epitome of human progress in relation to all other, lesser developed, civilizations. The Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano expanded on this idea of cultural repression and the colonization of the imaginary. He (2007:169) explains: “The repression fell, above all, over the modes of knowing, of producing knowledge, of producing perspectives, images and systems of images, symbols, modes of signification, over the resources, patterns, and instruments of formalized and objectivised expression, intellectual or visual.” What is meant by this is that part of Europe’s conquest strategy was to disrupt and deprave colonized peoples of their epistemologies, their ways of knowing. This is what constitutes epistemic violence. This was justified by the claim that, ontologically, they were not human beings of equal standing (Quijano, 2007; Ramose, 2021; Spivak, 1988). Instead they were considered sub-human, closer to nature, hypersexual, childlike, dirty, dumb, degenerate. Colonial science: Enlightened much? During the Enlightenment, western Science was heavily invested in creating the social hierarchies to support this colonial narrative, and anchoring it in a discourse of human nature (Foucault, 1975).[3] At the same time western science framed itself as objective, neutral, and universal. (You see what they did there?) This gave scientific knowledge the power of Truth (Foucault, 1975)! This produced a normalizing force and colonial control that was completely inescapable. Moreover, this type of knowledge was utterly Eurocentric, privileging itself over other/indigenous knowledge systems by marking the latter as primitive, folkloric, unscientific (Knopf, 2015). Originating from this history, it is no surprise that 200 years later the development sector is still largely structured around this form of epistemic violence and colonial thinking. So how should we, as young European professionals in this field, go about decolonizing the field as much as our own thinking? Exclusion in the development sector The omission of indigenous knowledge is inextricably linked to exclusion of indigenous peoples in the development sector as a whole. For decades we have viewed so-called developing countries as countries with a lack of knowledge and its individuals as beneficiaries who passively receive knowledge. And even discussions surrounding the decolonization of development cooperation are still Eurocentric. As Themrise Khan (2021) says: “The discussion around the decolonisation of aid practices is, in reality, extremely one-sided and Western-centric. It rarely includes the perspectives of those in the Global South. Many of us in the South do not agree with or relate to this terminology. In fact, we see it as a further imposition of a white saviour complex, with the powerful West once again deciding what is good for us and how this must be done.” According to Stephanie Kimou (in Cheney, 2020), founder of Populations Works Africa, the experiences and desires of people in ‘well-developed countries’ are prioritised in international development. We see this back in for example how monitoring & evaluation systems are set up, how funds are raised, and how stories are told. As Kimou says: “Rather than developing indicators that are important to them and their funders in Washington or Geneva, NGOs can ask the people they serve about how they define success and then design their programs accordingly.” In like manner, funders ask large INGOs to identify African partners that can implement programmes because they don’t trust locally-rooted organisations who have their own frameworks and ways of working (Kimou in Cheney, 2020). This is a pity because this is a missed opportunity to better understand local cultures and learn what works well in those particular contexts. Etuaptmumk: Two-Eyed Seeing - a solution? This existing Eurocentric paradigm is something that we, as young European professionals in this field, need to address if we want to contribute to a fairer and more inclusive world. That means that we can no longer do what Dominique David Chavez, a descendant of the Arawak Taíno in the Caribbean and a research fellow, describes as the western scientific tradition: “go into communities, get that knowledge and go back to our institutions and disseminate it.” Instead, we may adopt the indigneous approach of Etuaptmumk: Two-Eyed Seeing. Advocate and Mi’kmaw woman, Rebecca Thomas, explains in her Tedx Talk that Two-Eyed Seeing is about including different worldviews. “Two-Eyed Seeing takes the strength of both a colonized world and an indigenous world, and asks that the user sees through both lenses simultaneously… It is the Mi’kmaw understanding of the gift of multiple perspectives, to see multiple contexts simultaneously. … It’s not either/or. It’s both at the same time.” This requires us to play an active part in recovering and including oppressed (indigenous) knowledges in our development practice. Indeed, we would need to reinvent the sector as a space for participatory stakeholder engagement and collaborative learning to achieve sustainable impact. This stretches beyond simply patching up damages done due to centuries of (neo)colonialism by means of a fund or a nice statue. It means restoring the ontological status of Knower of ‘othered’ stakeholders and practicing our own ignorance.[4] Put simply, it means letting go of knowing it all. Then, perhaps, we may truly acknowledge each other. Then, perhaps, we may share our perspectives as equals.

References

[1] Look, for example, at the case of Saartjie Baartmans, the ‘Hottentot Venus’. Also for a reading of the relationship between Africa and the West through this figure: The ghost of Sarah Baartman lives on by Trevor Lwere (2021). [2] Ignorance here refers to ‘not-knowing’ in a sincere, curious manner. We should be wary, however, of reproducing the racist power structures that allow white people to wilfully claim ignorance on racism and colonialism. For more, read White Innocence by Gloria Wekker (2016). [3] For more on this, read this blog by Teba Al-Samarai and Jara Bakx (2021) on development and neocolonialism. [4] Jan Nederveen Pieterse (2010:16) claims that: “Conventionally development has been a monocultural project. Modernization and Westernization were virtually synonyms.” In addition, David H. Lempert (2014) explains how development is often framed in terms of linear progression toward creating modern industrialised societies. In the case of Vietnam, Lempert (2014:1, emphasis added) states: “Development of rural areas and of the peoples and their traditions appeared to have come to mean their elimination or destruction.”  Painting of an Ethiopian boy taking a shower. By Josphe, 2019 Painting of an Ethiopian boy taking a shower. By Josphe, 2019 Shifting the power, decolonizing development, localization... suddenly it is all over the place. And part of me is very happy with this development. Finally we are recognizing the power differentials that exist in international cooperation. Still it is important that we recognize it is a mixed bag with many interests playing up. Localization is not value free. Power differentials are also present at the local level. When I arrived in Ethiopia in 2001 the country was still dealing with the trauma of a non-resolved bloody war with its Northern neighbour Eritrea. Many Ethiopian port labourers, who had been deported out of Eritrea, had to reintegrate back home in Northern parts of Ethiopia, most of them in Wollo, a region infamous for its hunger crises of the seventies and eighties. To support this process my organization had lobbied the European Union to make funds available for this reintegration programme and I was hired as IDP program manager. Upon my arrival I was told the position was just successfully filled by a quite senior Ethiopian with an esteemed academic career. Subsequently I was asked to be his advisor. Obviously there was not much advise needed. I felt a bit like the boy in this painting of Ethiopian artist Josphe, taking a cold shower. In the end it turned out that there were serious concerns about misconduct and abuse of power, and I have played my part to address these concerns. But I can tell, it was an up-hill battle. In fact, being a foreigner, being still quite young, and having no prior experience working in Ethiopia gave me a 0-3 disadvantage right from the start. And to be honest, what weight did I bring to the job really? Still my earlier experience as a junior UN official serving a top-level bureaucrat in India, gave me the perfect preparation as also at that time it was made very clear to me, by this senior official, that I had very little to contribute and should be happy with having the chance to learn. This again was not far from the truth. Why I am telling you this story in an article about localization? First of all, the people involved have either passed away or are no longer in office. The reason for sharing this experience is to illustrate that a term like localization can be received differently by different people. It is our personal experience that colors the way we see things. When I hear people speak about the need for localization I have my concerns, especially when it comes to humanitarian work in conflict settings. While I recognize the importance of support via first responders who are in and from the community, I also realize that there are also local power dynamics that at times may compromise the humanitarian imperative. Hence, there are roles to play for international NGOs to ensure aid is provided in a fair and equitable manner. Proliferation of development NGOs At the same time I have witnessed the extreme proliferation of development NGOs replacing fundamental societal functions of home grown civil society organizations. I am therefore also very happy with researchers (also in Europe) who are increasingly calling into question the contributions NGOs make to democratization processes. To some extend they may also help erode democratic dividend as citizens may turn to NGOs for their rescue instead of turning to their governing bodies. It was shocking to realize that for people in rural Ethiopia there was basically only one word for any official visiting their area. It did not really matter whether it was a government official, a UN official or an NGO employee. They would all arrive in a four-wheel drive, talk to you briefly (often through an interpreter), and depart again and if you are lucky enough you would see them again with some resources to improve your situation al least for a while. So whose agenda is at work when we talk localization or decolonization of development. I belief still both represent very much the agenda of Western countries, with Kings and Presidents keen to admit wrongdoings of their predecessors while saying sorry. Dialogues start to emerge, different from the 'development briefings' of the past explaining certain agenda's. However, given the past, I wonder how much of a real dialogue is possible in the present. I wonder what the priorities of people really are if we are willing to be a fly on the wall. Not noticed and therefore the speakers not influenced by the presence of potential resource providers. We could be surprised what options they could think of. Development cooperation 3.0 I think it is high time for development assistance to mature into proper international development cooperation. This new type of cooperation would not focus on 'solving the poverty problem' in 'target countries' but it would aim to address inequalities around the world in the proper use of its scarce resources. It would be based on a respectful exchange of values, characterized by reciprocity with everyone willing to learn. This could lead to doing away with bad practice, improving on current practice while discovering novel practice that might help us making global and local development processes work for the benefit of all people and the planet. Back to Ethiopia, where currently the international community has difficulty reading the situation and struggled to take a position in the renewed conflict between people groups of which the scenery became the region of Tigray. On July 13, the Human Rights Council adopted a resolution calling for an immediate end to the violence and human rights violations in Tigray and ensure humanitarian access to vulnerable communities, as loosing out on two consecutive production seasons is likely to result in wide spread famine. Apart from this external pressure, crucial pressure is to be made domestically*. There is a silent majority of Ethiopians who want to see this conflict and many other tensions and conflicts in the country resolved and live peacefully together. They can organize themselves and use their civic space to voice their opinion and influence those in their direct surrounding or through social media (which are so often used counterproductively for spreading disinformation, stirring up the masses). They may be able to help society at micro, meso and macro levels to reconcile the present with the past. They have the ability and spiritual assets to shape new identities that are sufficiently anchored in the past, address systemic injustices, and are geared towards a shared future. If the international community is to play a role, whether mobilized by the diaspora or officially requested, it has to respect local ownership over the change process while upholding and defending universal human rights. * Local ownership is one of the principles embraced in the new OESO-DAC recommendation on enabling civil society, as adopted with unanimous vote during the recent Civil Society Days of the OESO-DAC. A couple of years ago, I had the priviledge to facilitate learning processes in the context of an international classroom setting. In those years I started a blog space called Walks and Talks, inviting experts and international students to contribute their perspectives. Reviewing some of these blogs I realised how advanced these ideas were and how relevant still today. The last contribution to Walks and Talks came from Mulugeta Dejenu, at the time an expert in Self Organised Learning from Ethiopia. While asking Mulugeta if he would be okay with republishing his contribution he responded: "I forgot how and when I wrote the bove. I read it through and still preserved the warmth it had a few years ago. .Self Organized Learning is an area that I enjoyed and wanted to expand. (...) It is a course that has to be supported in the future to challenge our robotic behaviour of learning." In a struggle to give shape to learning processes, Mulugeta and his colleagues were far ahead of many of us working in development cooperation. These are voices from the past that are worth reconsidering and put to use today counting on the possibilities of tomorrow.  Guest blog by Mulugeta Dejenu Capacity needs have systemic roots and are not isolated or standalone problems but rather interconnected parts reinforcing each other. This implies that capacity needs are interconnected and have to be addressed from a systemic point of view and not unilaterally based on a “wish list” of donors. How do we do that? What capacity is lacking? What are its systemic roots? How can effective learning being enhanced? How can we stimulate effective learning? These important questions will lead us to the basic philosophy of human learning. Over the last decade partner capacity assessments were done at different times, formally and informally with the purpose to identify key areas of support. The assessments that were done were mostly linear in their thinking, heavily focused on assessing gaps and suggesting unilateral solutions despite the capacity problems being systemic. Assessments often end up with endless wish lists. Those wish lists are often given to comply with or make happy those who made the request for them. The wish lists may not necessarily represent what the learners want. Solutions to capacity gaps are often addressed mainly through trainings, the topic, design and delivery of which were decided by the assessor of the capacity needs and not by the learner himself. This often leads to learners attending learning events that they do not want. From stakeholders perspective the impact of such training was not often as effective as needed. Capacity development is not about imparting skills and knowledge only but changing behaviours and practices to sustain them. It is the understanding of the key drivers of capacity development (CD) that makes the difference. Capacity Development is finding the right foci and a model that works and finding the right tools to support the modality, sustain it and scaling it. Again the drivers of CD inter alia are the intrinsic motivation people have to learn, where the energy and the desire come from the activity of learning itself and not from outside where it is extrinsically pushed. It is the liberty that learners have to be given to decide on their learning purposes (choices) and strategies that bring about change of behaviour and practices in human learning and not deciding what is best for them from without. "our learning purposes are negotiated from within our workplace, private or social life and determined based on their relevance to us as we see them fit and not someone from outside deciding for us" Learning is about being aware of one’s processes (task or learning processes), putting our customized behaviour of learning into conscious awareness. The freedom and choice to learn challenges our usual learning skills and enhances adaptive and reflective learning practices. This is because, our learning purposes are negotiated from within our workplace, private or social life and determined based on their relevance to us as we see them fit and not someone from outside deciding for us. Not only is the purpose of learning determined by the learners but the strategy and the evaluation criteria that they develop to monitor their own learning (the outcomes) and the review that they make at the end of each learning cycle. This brings us to the Personal Learning Contract (PLC) that the learner develops as opposed to the “wish lists” that do not in the majority of cases seem not to have direct relevance to what the learners want to learn about. The learning conversation that the learner makes within his mind and with his colleagues brings out his mental model “schemata” for others to critique it and in the process of which new insights and new meanings (learning) are formed. Learning is about a change of schemata or mental representations. It is an inference with evidence from experience, behaviour and can be nurtured through learning conversations and continual support. It is personal and can be accessed by the learner himself and to others when it becomes explicit during learning conversations. The learner can always access training as a resource in the pursuit of his own learning deciding which training courses he would like to attend (not imposed on him) and may also be shown in his strategy (PLC) of acquiring new skills in preferred fields. Those may not necessarily be the same as the external stakeholders have in mind. What a thought-provoking piece that would sit ery well with today's development debate around localization, shifting the power and decolonizing aid. A refreshing perspective from the so called South, challenging the North not to push their own agenda's when doing capacity development or strengthening civil society for that matter. A plea for self-determination also in terms of what to learn about and for what purpose, which results from actively negotating the individual, social, economical, political and moral. It is aimed at acquiring knowledge that builds on lived experience, embraces academic expedience and furthers sustainable and inclusive development.

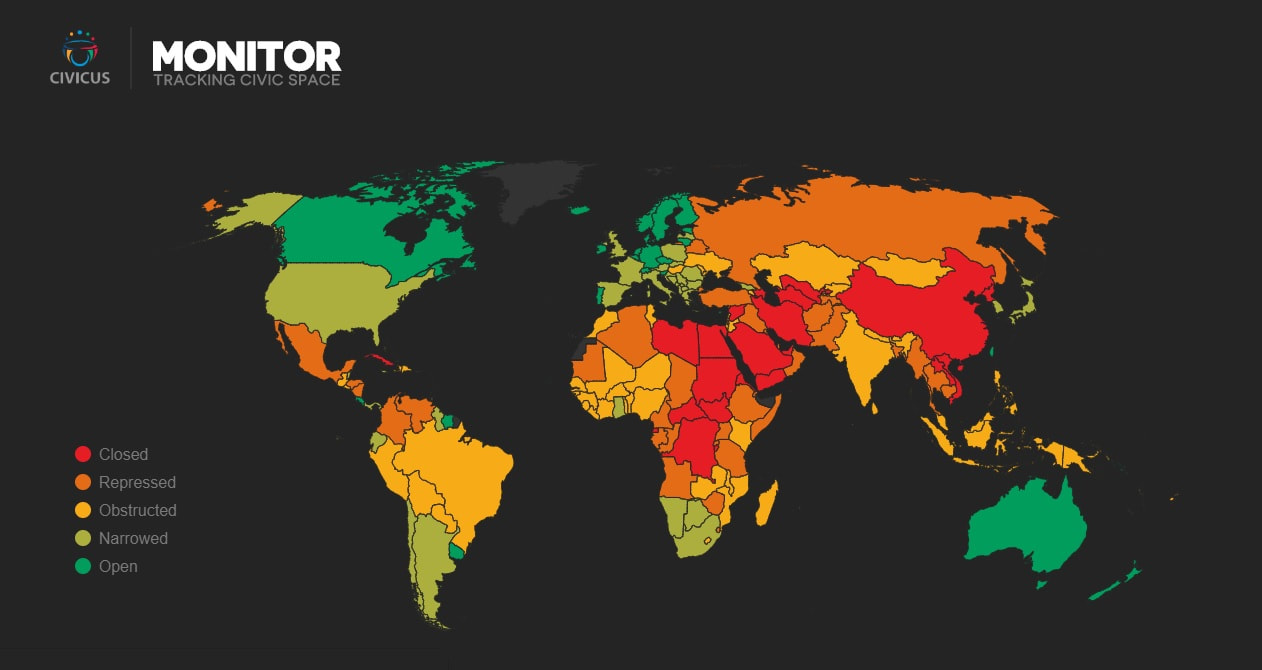

Ethiopian Art depicting the harvest season in Ethiopia (Makush Gallery, Adds Ababa) Ethiopian Art depicting the harvest season in Ethiopia (Makush Gallery, Adds Ababa) Last year, on this blog I published the CIVICUS civic space monitor. Recently, CIVICUS published an update, with civic space quickly disappearing. And if you are an expert on civic space that is an alarming statistic. However, if you are a civilian in the highlands of Ethiopia, civic space is probably the last thing on your mind. Your worries concern the amount of rain and the changing seasonality of it. Or the presence of a locust swarm that eats away your crop. Or that your labour force to harvest the crop is consumed by an armed struggle for self-determination, for better or worse. This may be the situation that a lot of people we met on the road last year may find themselves in during this harvest season. During Christmas holidays as a family we traveled through the highlands of Ethiopia and saw the grain being harvested and the oxes doing their threshing work while others were winnowing the grain by hand with help of the wind. In such a context what is the relevance of civic space? Has the current armed struggle anything to do with civic space, or the lack thereof? Or is something else at play? To answer this question one needs to dig deep into the history of people and places to understand first of all whose space we talk about and secondly how it links to the threshing and winnowing of grain. Screaming loudly about shrinking civic space, as many are doing, may not be the best strategy to get the message across unless you have a clear perspective whose space we are talking about; why we should pay attention to this space; how it is shrinking; and how it affects people's lives to finally arrive at the question: What can be done about it? During our trip last year we took note of the rich history of the Ethiopian highlands by seeing historic sites like Lalibela, Axum and Gondar enjoying marvelous beauty of nature and landscapes and friendly people. I cannot help but share a few pictures below. And though I had heard of the many changes to the road system in Ethiopia (including in its capital Addis Ababa) I was still surprised to find out how a journey from Addis to Dessie that 15 years ago took me a minimum of ten hours over a poorly maintained road was reduced to a six hours journey over a nicely paved road. The drivers were quick to point to all the new factories and/or horticultural farms that had sprung up during recent years and that had significantly influenced the local social economy, bringing a better standard of living for many formerly landless labourers. As we ventured out into the rural area of the highlands of Ethiopia it was harvest season and the grain had been collected and was threshed by the hoofs of oxes and donkeys, with Ethiopian men and women supporting them to keep going. This was mostly done on hilly places where they could subsequently easily separate the wheat from the chaff by just throwing it in the air, the so called winnowing. It struck me that this was still common place in most of the highland area of Ethiopia where mechanization was neither an option nor a desire for the small holder farmer.

Back in the Netherlands I found myself at a New Years reception at our Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Our Minister of Foreign Affairs did his level best to motivate us for the coming year to make a difference and not to forget about the perspective of the potato farmer in remote North-Holland whose export depended on our efforts to broker good export deals. During the Q&A session that followed I felt the need to also bring on board the perspective of the high-land farmer in Ethiopia that I had just met on the road. I of course referenced the 500.000 Ethiopian farmers that we had tried to improve productivity of (see 2018 Dutch development results report) and the close to 4 million households we had helped to stay food secure through a productive safety net program run by the Ethiopian government. So back to the question: Whose space are we talking about when we say that civic space is shrinking? Is it the small-holder farmer who sees his ancestral lands being taken from him with some financial compensation and leased to a foreign investor for a significant period of time, which is most of the time considered to be in the best public interest? Or is it the space of the factory worker who requires good labour conditions from the foreign investor, who was attracted by the availability of cheap labour? Or is it the space of the investor himself? Asking the question is also answering it. Each of them would benefit from increased civic space and all of them have seen it shrinking. Hence we may be talking about competing spaces. So let us examine, how does civic space look like for each of them. Civic space, according to Wikipedia, is "created by a set of universally-accepted rules, which allow people to organise, participate and communicate with each other freely and without hindrance, and in doing so, influence the political and social structures around them". However it continues to say: "It is a concept central to any open and democratic society and means that states have a duty to protect people while respecting and facilitating the fundamental rights to associate, assemble peacefully and express views and opinions." What if these rights are exercised by different groups with competing interests? The farmers who have a customary right to cultivate the land and have organized themselves, possibly with some public or private support, in cooperatives. They are facing the challenges of shrinking rural space for an expanding population. Lands may have seen over cultivation, and succession has been problematic since youngsters have been allowed to go to school and have come to know about other ways to earn a living that may allow them to explore the world a bit further. The landless people who did go out to the cities in search of employment were happy to find some employment in neighbouring commercial farms or factories. However, the salaries are just enough to live and too much to die and there are long working ours, whereas they still carry memories of low-season with abundant time to enjoy life. Finally there are those who remain unemployed for whom not a proper job exists and who lack the skills to create a job for themselves, hence they have to rely on petty trade and amongst them many girls may sell their bodies in order to feed their sibblings. In the meantime factory owners are facing increasing insecurity due to the large number of unemployed people that have to go out and steal their living together. Hence, how can all these spaces be negotiated when their interests seem to be so much in conflict with one another and peaceful co-existence seems impossible? Underpinning civic space is a strong social contract between governments and citizens. Shrinking space is often caused by a deteriorating social contract. Awareness about the lack of space or the absence of a social contract when investing in a developing country should be at the center of support provided to Dutch entrepreneurs who are venturing out into these for them unknown territories. Rebuilding that social contract as part of the investment strategy should be part of the equation and would be a great risk mitigation measure. In Ethiopia I have seen some entrepreneurs doing that very successfully, to the extend that local communities defended farms that were under attack of angry mobs of youngsters that lacked local opportunities and felt deserted by their own government. Also governments could invest in a better dialogue around utilization of natural resources and how to best serve the interest of the people. This dialogue should be supported by evidence about current land-use practices, as not all interests are always considered. Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships could be established with public and private entities meeting around some of these wicked problems and negotiating a solution that works for everyone. In the end the what is civic space boils down to the question: whose space are we talking about and could space of one group be limiting the space of others? Who should be mediating the potential conflicts? Here I do see a role for governments, civil society organisations and knowledge institutions, doing fact-finding missions around these conflicts. This may help re-establish a social contract that increasingly also needs to be made between different groups of people within society and governing bodies taking more of a facilitating role. In the end, awareness may raise that conflict will jeopardize everyone's space and will always provide a sub-optimal solution as conflict breeds conflict. Having a clear understanding of different histories of people and a clear view on the competing interests and having all of them considered at the decision-making table in a transparent and open manner may help to keep civic space open for everyone and make it productive towards a stronger social contract. In the end we have to live together in this world where there still is enough for everyone. However, also at global level this requires a new social contract between different people groups that allows us to know each other's history, coming to terms with the disparities that seperated us in the past and present and plan together for a more just global future where burdens are shared and challenges are faced together to the benefit of all. These are unusual times that demand unorthodox answers to the challenges we are facing. Yesterday evening our Prime Minister Mark Rutte made a very clear statement that has been long overdue since the outbreak of the Corona crisis. He first of all acknowledged the impact on children and youth of the crisis we have at hand as a global community. He then praised our kids and youth for their way of coping with the crisis and he ended with a clear invite to youth to participate in developing proper responses to the Pandemic. He also ordered our Mayors in all ciities to ensure youth is involved in thinking about solutions. The picture above, which illustrated youth participation in decision-making only a couple of months ago, just goes to show how their lives have been impacted dramatically.

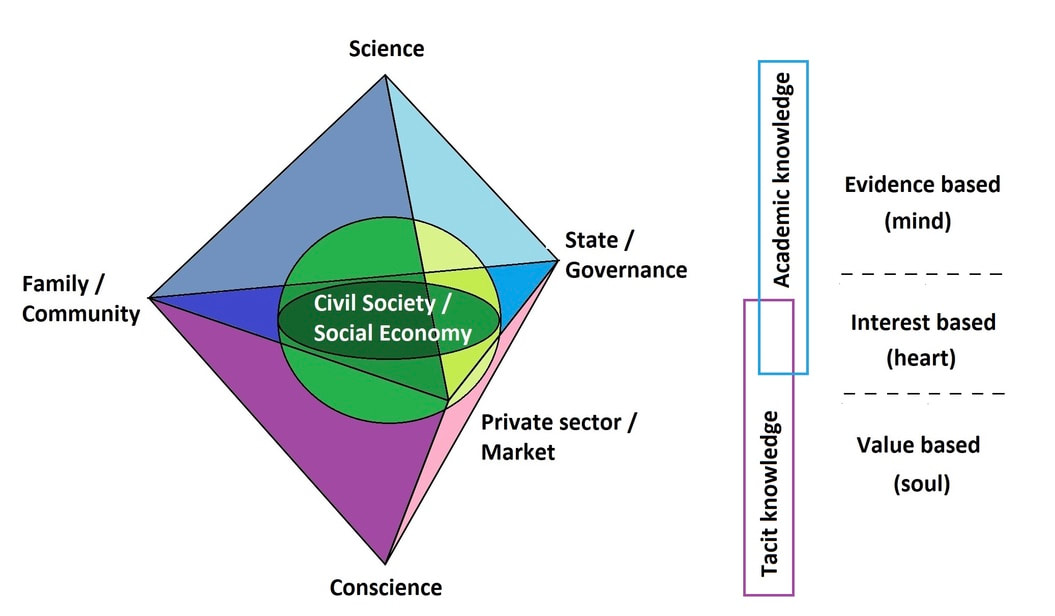

What a great way to engage the next generation, who have seen their prospects vanish in a very short time-span. Still, what a resilience youth is still showing. In my direct environment I am witnessing pregnancies, births, couples that make life-long commitments to each other, young people buying houses etc. Teenagers continuing their side-jobs in supermarkets and not refraining from filling the shelves while taking precautionary measures as prescribed by their employers while continuing their education online. They still connect with study-mates and take part in online sessions with study-friends while planning for their summer holidays to spend time with each other or doing something useful for society. In doing so, they signal to us how the world keeps turning though entire nations are held in lock-downs. Live goes on and life-impacting-decisions are taken despite an insecure environment and an unforeseeable future. Possessing the so called 21st century skills in abundance, would they not be best positioned to help us navigate a way out of the crisis? From June 1 onward, I have been asked to join a team in our Ministry that will support colleagues from thematic departments and selected civil society alliances to amplify in particular voices of youth, women and marginalized groups and to aim for safeguarding and strengthening civic space for the purpose of inclusive sustainable development. Something I have been advocating for since I have started this blog. What a privilege to be able to do so. We do witness both a global re-emergence of the state as a health and security provider and science stepping up in trying to bring the evidence to the table to understand patterns of the current pandemic while businesses alter their business models and find ways to mobilize technical support in finding solutions. We also see a vibrant civil society where people are helping each other to stay safe, going about their daily affairs somehow and adhere to rules that have been set and limit our freedom in public places. It is still early days to evaluate the effect this will have on global civic space. However, the pandemic did bring a new togetherness that we have not experienced for a long time illustrating the need to better work together internationally and learn from each other. Everyone is to give their best to overcome this crisis and also deal effectively with other crises that are still present at individual or communal level or those that are looming around the corner, like climate change. Like our Prime Minister I strongly believe young people can really help us out in developing lasting solutions. If we would only listen and include them in ongoing change processes. In the past couple of months I had some time to reflect on ten years of working with civil society organizations for humanitarian aid and development cooperation, while getting up to speed with my role at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs focusing on aid effectiveness. During my time working with civil society I have used Pestoff's triangle to conceptualize civil society space. It consists of three boundaries that separate the public and private domains, the for-profit and not-for-profit domains and the formal and informal domains. I came across this model in a partnership policy document of ICCO while preparing for a grant application back in 2010. It has since been a handy tool in furthering the dialogue around good governance, sustainable entrepreneurship and responsible citizenship. I discovered that also others have used it to identify spaces where public-private partnerships may emerge and to argue why civil society should be part of the equation (like Avelino & Wittmayer, 2014). However, during the last two years working with Tearfund, a faith-based NGO (FBO), I failed to demonstrate the relevance of the model to the overal theory of change of Tearfund and help them increase their engagement with institutional actors like market players and government agencies. Models like the one of Pestoff, find their origin in welfare state development policy and practice, with the state responsible for wealth redistribution. It insufficiently pays attention to indigenous institutions and/or faith systems which also deeply influence people's behavior and how they act as citizen, NGO-worker, entrepreneur or civil servant. Public agencies and secular NGOs increasingly realize that the domain of faith contains transformative power and is worth exploring. It is very much part of reality for a majority of people in developing countries (see a.o. contributions by Brenda Bartelink). It helps people to have a purpose driven life. Tacit knowledge, derived from these faith systems or oral traditions, may at times outweigh academic arguments in their ability to support or obstruct change. Observations are expanded from the known physical world into the unknown spiritual world with both worlds carrying competing truth claims influencing people's hopes and fears and giving them a sense of purpose. Adding science and conscience domains To accommodate both tacit knowledge as well as academic knowledge, I propose to add a knowledge dimension to Pestoff's model. It adds two domains to the model, the domain of science and the domain of conscience, with a hybrid space in between. The conscience domain has been developed over centuries of human experience and transfers from one generation to the next and stretches out from the known into the unknown. It is enshrined in holy texts and has been codified in declarations like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Faith in whatever form or shape extends the furthest into this unknown territory, claiming a kind of knowledge that is based on a revelation of divine promises and rather validated by human experience than by scientific proof. Inclusion of both knowledge dimension turns the Pestoff model into a 3D model adding a fourth hybrid boundary between academic and tacit knowledge that also constitutes civil society. Civil society is the space where both people's value systems as well as academic research contribute to a global conscience that leads to negotiated goal setting. In yhis space academic knowledge has a role in validating some of the knowledge derived from tacit knowledge while also exposing flaws in thinking. Likewise tacit knowledge may put necessary restrain on scientific advancement, where research objectives have no societal contribution or where research methods are considered unethical.

Islands of predictability The Sustainable Development Goals were born in this space and serve as reference points for our global conscience. Especially governments and companies aiming for short-term profits will be quick to question the realism of these promises and would prefer others to deliver on them first. Philosopher Hannah Arendt already stated in her best seller The Human Condition that international treaties serve as "islands of predictability in oceans of insecurity" (Hannah Arendt 1957). in order for the SDGs to be delivered on, civic space needs to be maintained and increased as much as possible aiming for convergence of objectives from the other domains towards sustainable development. Can we measure changes in civil society space? Mathematically it remains virtually impossible to calculate the size of civil society space, which has been a challenge as long as the concept exists. Boundaries of civil society remain blurred on each of the dimensions with a lot of hybrid space surrounding it. Hence the model still won't resolve the challenge of measuring civil society space. Nevertheless I hope this adapted version of the Pestoff triangle helps in furthering the thinking on aid effectiveness, paying due attention to the contributions of both academia and indigenous knowledge and/or faith systems and actors while developing common goals that will help shape a purpose driven international development practice. In the past week leaders met in New York to reflect on progress on Agenda 2030 during the High Level Policy Forum on Sustainable Development. While implementing Agenda 2030 the potential power of purpose cannot be overestimated. Development cooperation is known for approaches that value goal setting. Many practitioners in development cooperation are quite familiar with the logical framework approach (which was developed by USAID in the sixtees). I got it introduced to me in a Project Cycle Management course by MDF in the ninetees. where it was called Objective Oriented Programme Planning (OOPP). It was introduced to me with its German name ZOPP: Zielorientierte Projektplanung. I could not find an etymological connection between the German word Ziel and the English word zeal, which originates from the greek word Zelos that is understood as the fervour or tireless devotion for a person, cause, or ideal and determination in its furtherance. The German word "Ziel", which is translated as goal or destination, still pays tribute to what I consider an important contributor to achieving results: The willingness to get there. Rhineland and Anglo-Saxon features The Logical Framework approach has been considered too rigid though its planning rigor has been widely recognized. What is often forgotten is that the approach was to be complemented by a proper problem analysis to establish the interlinkages between symptoms, problems and root causes. A so called problem tree is an important intermediate step in developing a logical framework . And according to the German ZOPP it is to be informed by a SWOP analysis. Yes this is not a typo. It is again a subtle difference between the Rhineland and Anglo-Saxon approach in managing for results. SWOP is used in Germany and stands for Strength, Weaknesses, Obstacles and Potentials. Here again I like the German choice of words over the Anglo-Saxon SWOT analysis that uses Opportunities and Threats instead. A preference for flow and energy over a rather opportunistic and defensive winner-takes-all approach. This approach is also favoured by Brian Levy in his book "Working with the grain. Integrating Governance and Growth in Development Strategies" that he wrote in 2014, partly inspired by Douglas North's "'adaptive efficiency". Levy articulates an approach to development that is more considerate to chaos. Levy introduces the book as an exploration on the meeting of theory and action. This is also a critical element in a Theories of Change approach where assumptiona are a more pronounced part of the intervention logic and also subject to monitoring. A "with-the-grain" approach conceptualizes change in an evoluationary rather than an engineering way.o

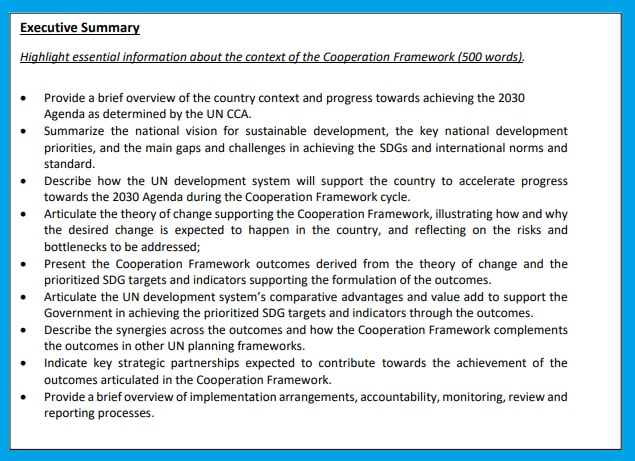

The deliberations in New York showed that the critical mass has not been mobilised yet, resulting in insufficient progress on many of the Sustainable Development Goals. In Theories of Change assumptions are made a.o. on contributions of others, finances being leveraged, capacity being developed or already in place etc. However, what if these assumption turn out to be false. What if sufficient money is available but not sufficient capacity to deliver? Going with the grain may not always work out well. It may be a good advise in change trajectories that only require minor corrections. However, what if radical change is required? Will the world be able to get their acts together or is everyone looking to each other for making the first move? Increasingly citizens turn away from governments as they no longer belief they are of much help in protecting the public goods. How can confidence in the multilateral system and governments in general be restored and public interest regain its primacy over individual country ambitions or personal gain? Unified country cooperation frameworks It is good to see that the UN finally has embarked on unified country development frameworks using a Theory of Change approach. The aspiration is to deal effectively with vested interests of individual UN agencies. Most importantly it should lead to a country-lead results framework that will improve mutual accountability while honouring alignment and country ownership ambitions that were already formulated in Paris back in 2005. If the UN will be successful in doing so, it is up to the bilaterals to follow suit, and ensure that their efforts support country systems and the multilaterals in a common strive to deliver on the Sustainable Development Goals. In the context of international development cooperation this will require from individual agencies as well as individual countries to put cooperation and collaboration ahead of competition and organizational or national interests. A true recognition of ones own limitations is as important as knowing the specific value add one can bring to the table.

Mobilizing all resources Despite the efforts to bring different resources and capacities together for a common cause, something else seems to be needed on top of it. This something else may be closer to a common purpose than a common cause. Could there be alternative futures to the doom and gloom scenario's that currently dominate the discourse? This is where the theory of change approach comes in strongly as a tool to formulate desired outcomes. It is not only about the results we achieve, but it is first and foremost to what outcomes they contribute. A purpose driven development cooperation needs to tap into all people's resources, including abilities, intellect, ambitions, inspirations and hopes. Like the poster of a basketball player my son used to have at the wall of his bedroom with a quote of Ralph Emerson: "The task ahead of us is never as great as the power behind us."  Today and yesterday were the days of Pentecost. The days that many churches around the world commemorate the descend of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles and other followers of Jesus. Though for many development professionals from Western societies this reality is something from a distant past, it represents spiritual capital that many other countries still have in abundance. I was pointed to the term spiritual capital by a colleague involved in the third SDG status report of the Netherlands. The report mentions having a philosophy of life as an important driving force for action. It was acknowledged that attention to this aspect has long been overlooked in sustainable development policy-making. Interest in spiritual capital is on the rise according to the authors of the report. Religions have traditions of poverty reduction, healthcare and education. Pope Fransiscus and 'green Patriarch' Bartholomeüs were mentioned in relation to their call on believers and non-believers for ecological and social responsibility. Back in 2014 the Dalai Lama paid a visit to our country with a message about education of the heart which challenged the way our education systems are wired. According to the Dalai Lama our educational systems are oriented mainly toward material values and training one’s understanding. But reality teaches us that we do not come to reason through understanding alone. We should place greater emphasis on inner values. Faith may also be an obstructing force as was mentioned in the same SDG report, as women and girls are often denied opportunities for self efficiacy as a result of religious norms. In my own church denomination in the Netherlands for instance only this year functions like pastor, elder or deacon were opened up for women. Though for some this illustrates the slow pace for change within faith systems, it also demonstrates that emancipatory forces do not by-pass the church. Change will come inevitably. The question is: do we have spiritual literacy to mobilise spiritual capital for achieving sustainable development outcomes? Knowing that 80% of the world's population would call themselves religious this seems to me a very relevant question. Religion and development The Amsterdam Centre for Religion and Sustainable Development at the Free University will bring out an annual report on religion and development under leadership of Prof. Dr. Azza Karam. Dr. Karam served recently as senior advisor on social and cultural development at UNFPA, where she coordinated the outreach with faith-based partners. The Dutch-Egyptian influencer was also chairing the UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Religion and Development that brings out an annual report on Faith linkages to the UN containing an impressive list of resources. ‘At present our educational systems are oriented mainly toward material values and training one’s understanding. But reality teaches us that we do not come to reason through understanding alone. We should place greater emphasis on inner values' Dalai Lama It seems the Netherlands is just waking up to the potential of its spiritual capital. For long faith-based NGOs were treated with some healthy suspicion as they were known for missions intertwined with proselytism, which remains a key-exclusion phrase in allocating government subsidies. However, what spiritual capital did we lose in the process? Could faith be an entry point for change? Which values are formed and what behavior is learned and what new insights are gained in the realm of faith that can be leveraged for sustainable development?

UNFPA has since long recognized the need to engage with faith actors when it comes to issues around family planning, stigma and discrimination, sexuality education and the like. In 2009 they developed guidelines to help their staff engaging with faith based organizations as agents of change, which they considered vital for implementing the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994. More recently a new Partnership for Religion and Development (PaRD) has been created, providing for an interface between faith-based NGOs and the donor community. Putting spiritual capital to use There is a danger however in mobilizing spiritual capital for developmental purposes. In a sense organizing special conferences or side-events around religion and development could contribute to a siloed approach to faith-based development as a special track, with a separate (often private) funding base and corresponding private accountability requirements. Lack of checks and balances within the church for instance caused religious clergy to exploit their constitutencies for their own material gain or to increase the wealth of the church administration. Many basilics across Europe testify to it. This has turned the church into one of the material power houses of this world. Today this orientation may still be found in Orthodox as well as Evangelical corners of the Christian landscape, from the Ethiopian Orthodox Church collecting from the general public for their majestic church buildings to the Evangelical Prosperity mega Churches in Nigeria that are very influential in West-African Christianity. However, the spiritual capital in most may be burried in the process. Christian communities could rediscover their spiritual capital and put it to use for the community as it has been there right from the beginning from the days of Pentecost: "They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need" (Acts 2:45). The purpose of giving clearly was not the church but were people in need. It is not that they sold everything, but they did get rid of abundance in order to provide for the needy and these initiatives spiraled out of control in the end becoming an existential threat to the Roman Empire. Praying in spirit and truth Studying contemporary and historic Christianity through these lenses helps to rediscover the spiritual capital hidden in faith itself. It requires religious literacy which in my case I somehow received in my Christian upbringing (with of course some terrific blind spots for potential contributions from Buddhism, Humanism, Islam and the like). For instance in the gospel story of John, where Jesus speaks to a Samaritan woman at Jacob's well in Samaria. Not only is it quite unusual that he speaks to a woman, it is even a woman from a different ethnic group (the Samaritans) with whom the Jews of his days were not on speaking terms. However, the conversation quickly tells her that she is talking to a prophet, which makes her ask the burning religious question of those days: Where to pray? In Jerusalem or in Samaria? Jesus' answer is even more remarkable and still carries meaning for our days of pentecost: True worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and truth. God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth. These words go way deeper than an answer to an obvious relevant question at the time. This answer helps me even today reaching out to other faiths and world religions. In fact while living in India and Egypt and later in Ethiopia I have discovered praying in spirit and truth is potentially available to every human being, even if it takes the shape of a curse or condemnation. Creation or evolution, a matter of truth or spirit? In the past year, within our church community, some people had quite an issue with a sermon that our pastor held in September 2017 combining the story of Genesis with evolutionary approaches in helping us to further our understanding of the first chapters of the Bible. Not by comparing and contrasting them to finally point to one option. But to accept both the revealing power of the Holy Scripture confirming God's acts of creation as well as acknowledging years of scientific studies into evolutionary principles and academic insights derived from it. Not so long ago a sermon like this would confront the believer with a choice for either the creation story or the evolution theory. Nowadays, both perspectives may co-exist, with academic insights complementing theological perspectives and even deepening appreciation of the complexity of creation and the evolutionary processes that are part of it. Knowledge and faith going together mutually re-enforcing each other. How to bring spiritual resources on board? Having worked with a wide variety of development actors I have sensed the Spirit at work in many hearts of committed colleagues, disregarding their religious background or personal convictions. I have no difficulty in finding common cause with a progressive humanist who would be at the barricades for the acceptance of sexual minorities nor with a Muslim colleague working for a humanitarian aid agency. I am in favour of a radical inclusive approach. My ideal international development organization would include people from all walks of life engaged both in aid provision or development work, working side by side, each tapping their own personality, intellect, skills and spiritual resources being able to connect to different groups in society. Also on the receiving end I would like to see people regaining dignity and rediscovering their god-given potential and therefore local capacity (from whatever ethnic, social or religious grouping) would always need to receive primacy over external technical support. That support should be indiscriminatory, knowledge driven and culturally-sensitive, value based and implemented in accordance with internationally recognized standards of impartiality and aid effectiveness, in particular when it comes to humanitarian aid. I belief I have recently joined such an agency, that I am happy to be part of and contribute my perspective to while learning from others. The debate as to how aid is to be provided and how one is to be aided will never end I suppose. In the Netherlands we are blessed with a sector quarterly (Vice Versa) that also brings out special editions. Though media neutrality may be questioned a bit, since these special editions are sponsored by particular aid agencies wanting to spur the debate on a topic deemed relevant for their cause, it helps digging a bit deeper into specific subjects. This Spring's edition is entirely devoted to Change the Game Academy, a programme of Wilde Ganzen (Wild Geese). Change the Game Academy is supporting local organizations to amplify their voice in local advocacy efforts, signaling the increased attention paid to local game changing capacity and home-grown civil society development. The question that came to my mind is: "Is the game really changing and if it is, who are really changing the game?". What is certainly changing is organizations advertising each other's approaches. ICCO introduces the Change the Game Academy of Wilde Ganzen on its web site as follows: "Change the Game Academy is an innovative program that helps civil society organizations all over the world, mainly in the global south, to learn to raise funds locally and to mobilize other kinds of support". This is not just a nice guesture of a like minded agency, but it is the result of Dutch organizations working together in alliances as a means to access co-funding from the Dutch government in what is called a strategic partnership. So question is: who is changing the game here? Global civil society Civil society is under pressure globally as Siri Lijfering reports in the same edition, as she is quoting the State of Civil Society Report of CIVICUS. Civil society has been understood as the arena between the public, the private (market) and the informal (family) domains where people advance common interests (Heinrich 2004:13). However, it appeared tough to quantify this space, despite attempts with a Civil Society Index. More recently the CSI has been replaced by a worldmap color coding civic space using five broad categories: closed, repressed, obstructed, narrowed and open. It resembles the way in which FEWS-net tracks food insecurity around the world and helps in having a birds-eye view of civic space and where it is mostly contested. The word that features frequently in the CIVICUS report is 'power', fitting the concept of countervailing power that is often associated with civil society. However, as is illustrated by the narrative reporting on the state of democracy, (part 3 of the report) the likelihood of civil society being seen as supporting opposition forces is quite high. In his contribution to the same Spring-edition of Vice Versa, Fons van der Velden, director of Context International Cooperation, argues that western models have dominated the discourse, stating that the traditional distinction between government, private sector and NGOs no longer holds with many hybrid organizational forms starting to emerge. Though I agree with his analysis, I would argue that maintaining analytical rigor helps in doing trend analysis. For instance having used the Pestoff Triangle with international students to identify the status of the civic space at home for many was an eye-opener in understanding the dynamics at play in their societies. Quite often these dynamics were a result of foreign interference. Western concepts of good governance and state building for instance have promulgated a certain governance that furthers the primacy of the state in favor of regional stability but at the expense of customary rights and self-determination by people groups that co-incidentally (and sometimes even temporarily) reside within national boundaries. In many instances this has turned the state into a predatory force against its own local people groups that have limited ability to protect themselves. In such instances it is justified to support opposition forces that try to tame the state and promote local and customary governance to take primacy over central governance. African election victories often serve to replace one minority government with another, as clientelism persists.

Our turn to eat The underpinning 'Theory of Change' is best illustrated by the book "It's our turn to eat" written by Michela Wrong in 2009 and recording the story of whistle-blower John Githongo in the run-up to Kenya's elections in the end of 2007 (then Minister Agnes van Ardenne from the Netherlands reportedly being the only donor freezing aid over corruption concerns in 2006). From this book and its successive reviews and talks it is clear that donors are often as much part of the problem as they could be part of the solution. As the CIVICUS report illustrates, in Europe similar challenges are posed to democracy with right-wing groups capitalizing on feelings of loss of control, diminishing prospects for a meaningful life and fearing loss of identity. Added to that is a substantial European bureaucracy which is portrayed as a predatory force, that would not be inclined to sufficiently serve the interests of its individual member states. Question is of course: Are European policies predatory or do they serve a common interest that cannot be dealt with by individual states? The British people must realize by now (probably too late) that the latter also is at stake. This same question will need an answer in settings in developing countries. Whose interests are being served? How is power being granted and how is it being used? This should also be asked about the added value of foreign agents (governments, companies or NGOs alike) in developing countries. Diplomatic missions clearly have a mandate to advance the interest of their governments and supporting their citizens working in the country concerned. However, what about the development wings residing in these same diplomatic missions, directly benefiting from diplomatic protection. Will they be able to see beyond their national interests and advance the interests of the target country with intervention strategies that serve their host countries' interests? Or has the aid agency turned into a trade agency where favors to governments in terms of development funding are exchanged for favorable trade deals? Can trade and aid really go together? And what to think of other nations with similar objectives having their entrepreneurs and citizens also benefiting from globalization and business opportunities abroad? It is indeed high time for the game to change. Van der Velden compares the current pack of development agencies to the orchestra on the Titanic that keeps playing while the ship is sinking. Van der Velden points to the need for innovation and the lack thereof with mainstream development agencies that still live by old paradigms. Learning and adaptation capacity is limited while according to van der Velden in essence the question that needs to be addressed is one of bringing together power and servanthood. As long as money exercises power over recipients of aid real reciprocity won't be an option, as also illustrated by the story of Ellen Mangnus in her column in the same volume where she discusses the financial support she still provides to her research assistant in Mali (while the job is already done). In order to break this deadlock van der Velden points in the direction of social impact bonds which would increase ownership for local aid agencies or social entrepreneurs. Question is: What remains of international development cooperation if it becomes evident that advancing local interest can only be done when local ownership is fully exercised? Indeed it becomes a privilege to be allowed to witness local innovation, entrepreneurship and development that is anchored in local capabilities and opportunities. Another question that comes to my mind is: Can we still speak of truly endogenous development or have external forces already been imprinting their 'development' trajectories onto local people group's? Changing the terms of trade Lastly, I won't see landlords giving up their privileged positions easily. In-equality is already as much built-in at national levels as it is globally. It is national governments that are often exploiting their own peoples, residing within their national boundaries and depriving them from their ancestral lands while tresspassing customary rights, making deals with predatory foreign investors, using scorched earth tactics while benefiting from impunity. The only power that can persuade them are the powers of market forces. If conscious consumers no longer buy their products they have to wield power. Elephants and rhino's will stay alive if Chinese demand for ivory would stop. Wars in central Africa will no longer be fought when only conflict-free coltan will be allowed access to the global market. Poor people will stop cutting trees if they are able to generate their energy or household income from more sustainable resources. For this global change of mindset the terms of trade should be re-established at a global level, induced by the sustainable development goals already agreed in New York. Results based financing should inspire sustainable trade deals and aid with lasting impact, thereby maximizing efficiencies in reaching them as time for change is running out. Van der Velden observes four challenges: 1) North-South thinking still dominates the discourse while challenges have become global (climate change, stress migration, insecurity). 2) Underestimating local capacities for change 3) Lack of reciprocity in partnerships 4) Lack of expedience (or Theory of Efficiency), which according to van der Velden could be developed by increasing direct support to local agencies. While I support the first two challenges, I would argue that the other two challenges only go to illustrate the presence of the denounced North-South thinking. What is required in my view is quality global connections, preferably triangular of nature. Where the China-Africa axis is kept in-check by proper EU-China and EU-Africa relations for example, all combining sustainable aid and trade lenses. It should help deal with power differentials caused by differences in knowledge and expertise which are distributed over the various nodes of the network through triangulation and will need to be geared towards the preservation of the planet for future generations. This would require inclusion of actors of all hemispheres while acknowledging that resources to achieve the objectives are by nature shared resources (be it natural, financial, social, physical or human capital - compare the DFID Sustainable Livelihoods Framework, 2000). Power and servanthood This indeed requires a coming together of power and servanthood as is also the plea of van der Velden. I have seen such attitudes develop from relative close range with various agencies, including with Wilde Ganzen. Especially the younger generations are much more able to cross boundaries and collaborate, beyond organizational and institutional boundaries. Voices from the south are amplified to the north rather than the other way around. It is the realities that people are facing on the ground within the confinement of unfair production systems that is reaching the consumer nowadays mainly through their peers in networks that link them up locally as well as globally in close collaboration with media organizations. Peter van Lieshout in his advice to the Dutch government entitled "Less Pretention, More Ambition" already concluded in 2010 that the question about how investment in civil society contributes to development remains largely unresearched. However, I am pretty sure that one of the proxies to measure the strength of civil society is the number of quality connections between civil society actors and their international peers not marked by a contractual arrangement but rooting in a common drive for change. A localization agenda while global changes are sought after seems to me counterintuïtive to this ambition, despite the laudable purpose behind it. Increasingly we should stand togerher as civil society partners across the globe and call our governments to account and put pressure on industries through influencing consumer behavior. In turn this will lead to better global development outcomes which should be measured in terms of efficiency and effectiveness in the light of the global development goals as agreed in New York in 2015. I am glad to increasingly seeing diplomats wearing the sustainable development goals pin on their chests rather than their national flags. I hope that results based financing will indeed be expressed in terms of contribution to the realisation of these global objectives. As Rheticus, a 16th-century mathematician and cartographer, stated “if you can measure something, then you have some control over it.” Or as management guru Peter Drucker later stated slightly popularized: "What gets measured gets done." Freely you have received, freely give At a very local level in my home church I am happy to already witness traces of reversed 'aid', with Indian pastors coming over to the Netherlands in the coming month to teach our youth workers and share some of their experience with community outreach. This may sound a bit strange to secular ears, where misplaced fear of abuse of official development aid for purposes of proselytism abroad is nowadays replaced by fear of proselytism by foreign powers to spread their religion into our society in the Netherlands. Can you imagine how Dutch churches these days are in need of 'support' from their brothers and sisters in India to re-assess their own religious assets and re-value concepts like being a good neighbor, rather than sticking together as faith communities and taking care of one self and one another while forsaking the community they are part of? I would therefore like to encourage Ellen Mangnus to continue her support to her Malinese research assistant when it continues to support his/her development and strengthens the mutuality of their relationship if she is willing to also receive the many blessings bestowed upon her in exchange for her financial gift. I recall my Indian friend telling me years after my parents donating a fridge to his family that he had prayed for me every day since. I wonder whose gift was greater. - On May 24 Vice Versa organizes a debate on Changing the Game - details will follow soon - |

About meMy name is Reinier van Hoffen. U®Reading

Click here for a summary.

Also find the text of a lecture Dr. Achterhuis held at the 2012 Bilderberg conference. Archives

August 2022

|

AddressNachtegaallaan 26

Ede, the Netherlands |

Telephone+31 (0)6 1429 1569

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed